I’ve always been captivated by medieval manuscripts and the monastic movement behind their creation. Movement that in many ways shaped Western civilization as we know it today. The quiet discipline of scribes, the flickering candlelight reflecting off gold-leafed pages, and the intricate beauty of illuminated manuscripts have always stirred my imagination. In a way these weren’t just books, they were sacred labors of love, crafted to preserve and proclaim truth in a world long before printing press, computers, and pixels.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit an exhibit called Symbols and Signs: Decoding Medieval Manuscripts, where I stepped into that world and explored firsthand the mysterious symbols and hidden messages woven into these ancient texts. It was an amazing experience, like unlocking a centuries-old code carried across time.

The exhibit explores how medieval manuscripts used complex “codes” to communicate meaning, through words, images, and schematic systems. While these codes may seem confusing to modern audience, they once conveyed layers of meaning to readers deeply immersed in the cultural symbolism of that time. To simplify, they were like emojis and abbreviations we use in texting today, symbols packed with meaning for those who know how to read it.

Word Codes

In medieval Europe, written text was often more than just words on a page. The scribes transformed letters into art, twisting, weaving, and embellishing them until they became part of the visual picture. Latin, Hebrew, and Armenian alphabets were common, but their ornate forms could be difficult to decipher even for contemporary readers.

These manuscripts featured abbreviations, monograms, and acrostics that acted like riddles for the reader. The playfulness and challenge of decoding these texts created a more interactive experience with the sacred or scholarly content they conveyed. In a sense, every manuscript was a puzzle waiting to be unlocked.

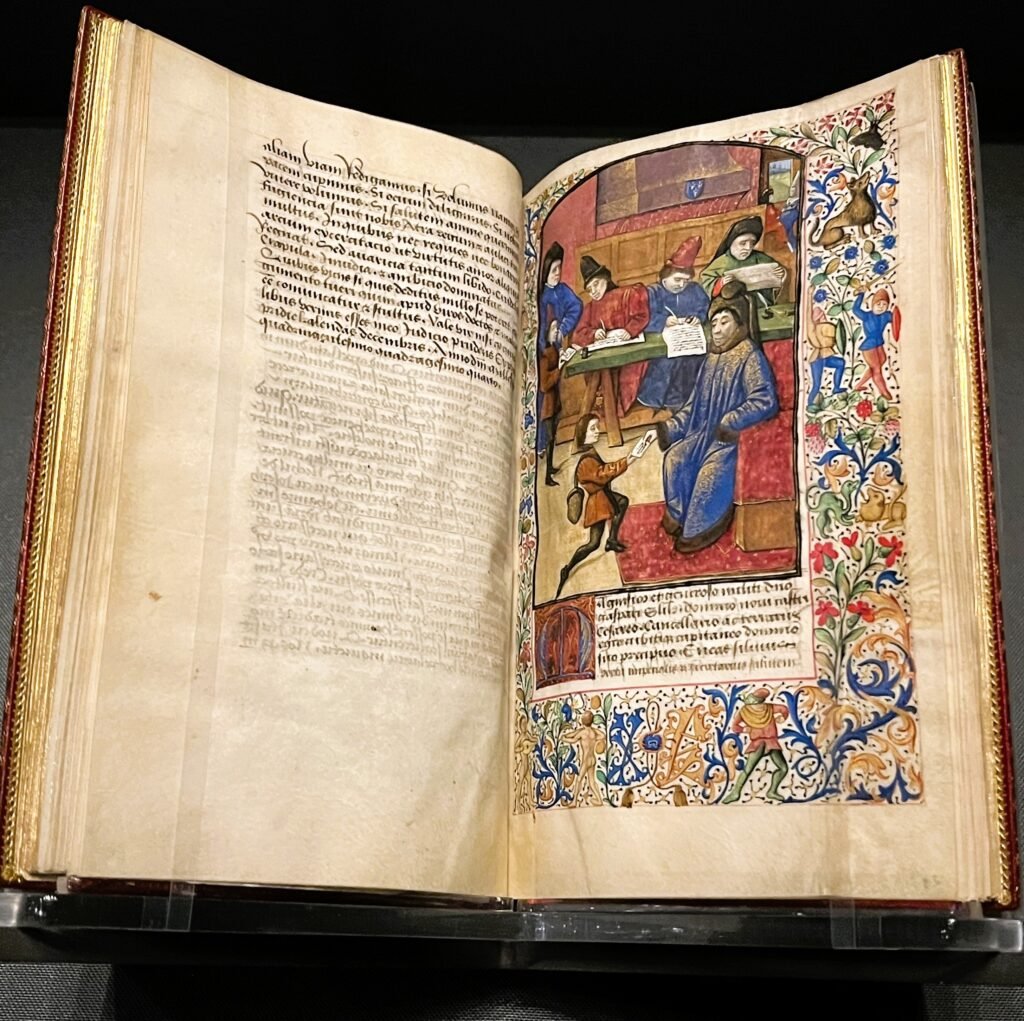

A Messenger Delivering a Letter | Date: about 1460-70 | Country: France | Artist: Unknown | Author: Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini | Text: Letter to Johann von Eich (in Latin)

This image above of busy scribes writing at a desk accompanies a letter recounting life at court. The manuscript was commissioned by Charles of France (1446-1472), son of King Charles VII. His identity is encrypted in the intertwined letters in the bottom border.

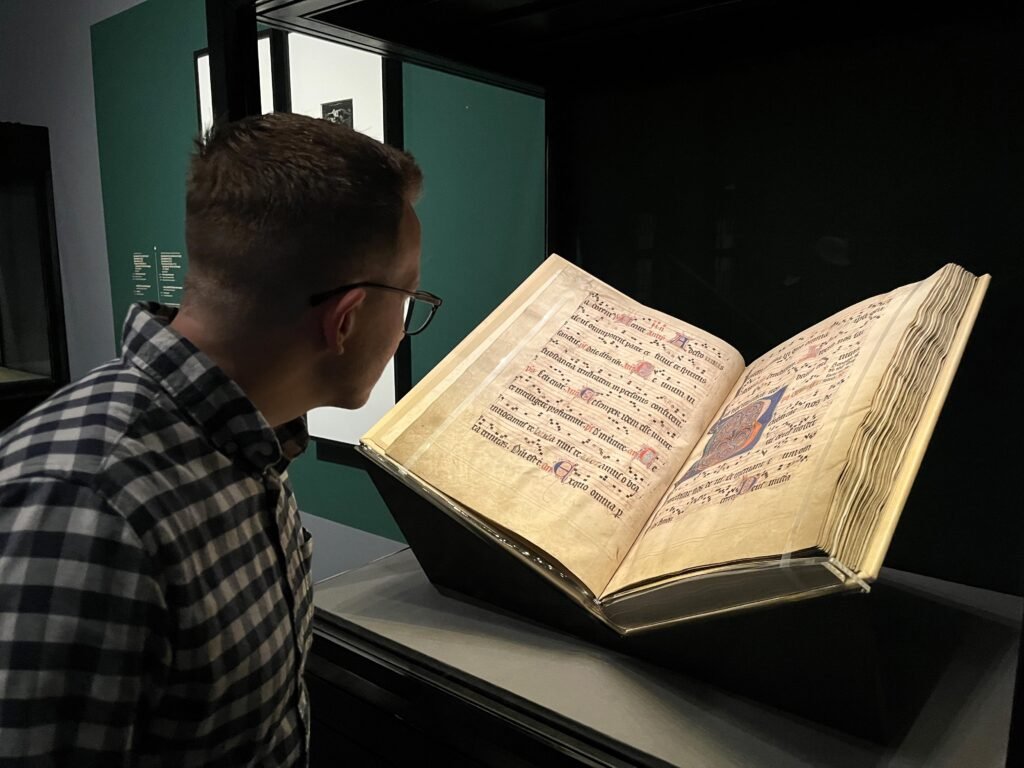

Inhabited Initial IN | Date: 1153 | Country: Italy | Artist: Unknown | Text: Breviary (in Latin)

The artist of this book playfully mixed visual and textual components to capture the reader’s attention. On the page at left, what appears to be an abstract, whimsical decoration is in fact a cleverly interwoven pair of letters, I and N, the start of Psalm 86 in Latin: Inclina, domine, aurem tuam (Incline thy ear, O Lord).

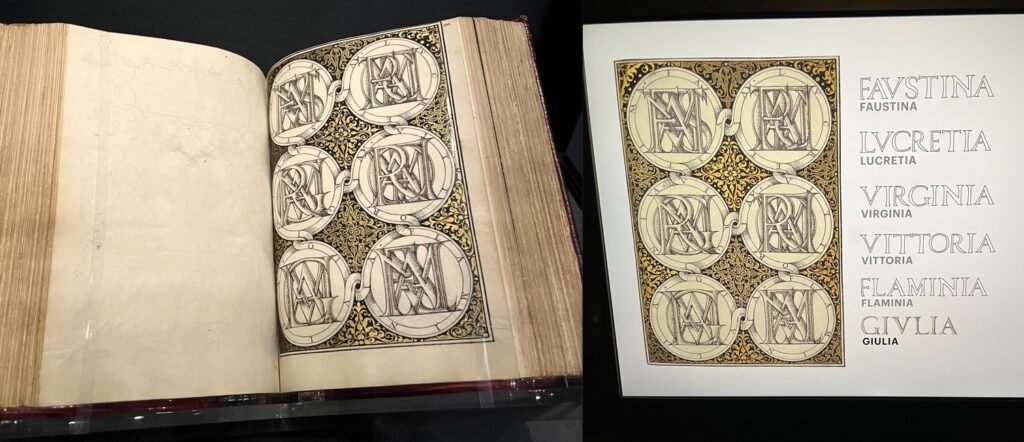

Names Written in Superimposed Letters | Date: 1561-62 | Country: Austria | Artist: Georg Bocskay | Text: Model Book of Calligraphy (in Latin)

Building on the medieval tradition of intertwining text and image, Bocskay, the calligrapher of this book, puzzled his viewers by presenting the names of six famous women of ancient Rome in stacked, or overlapping, letters.

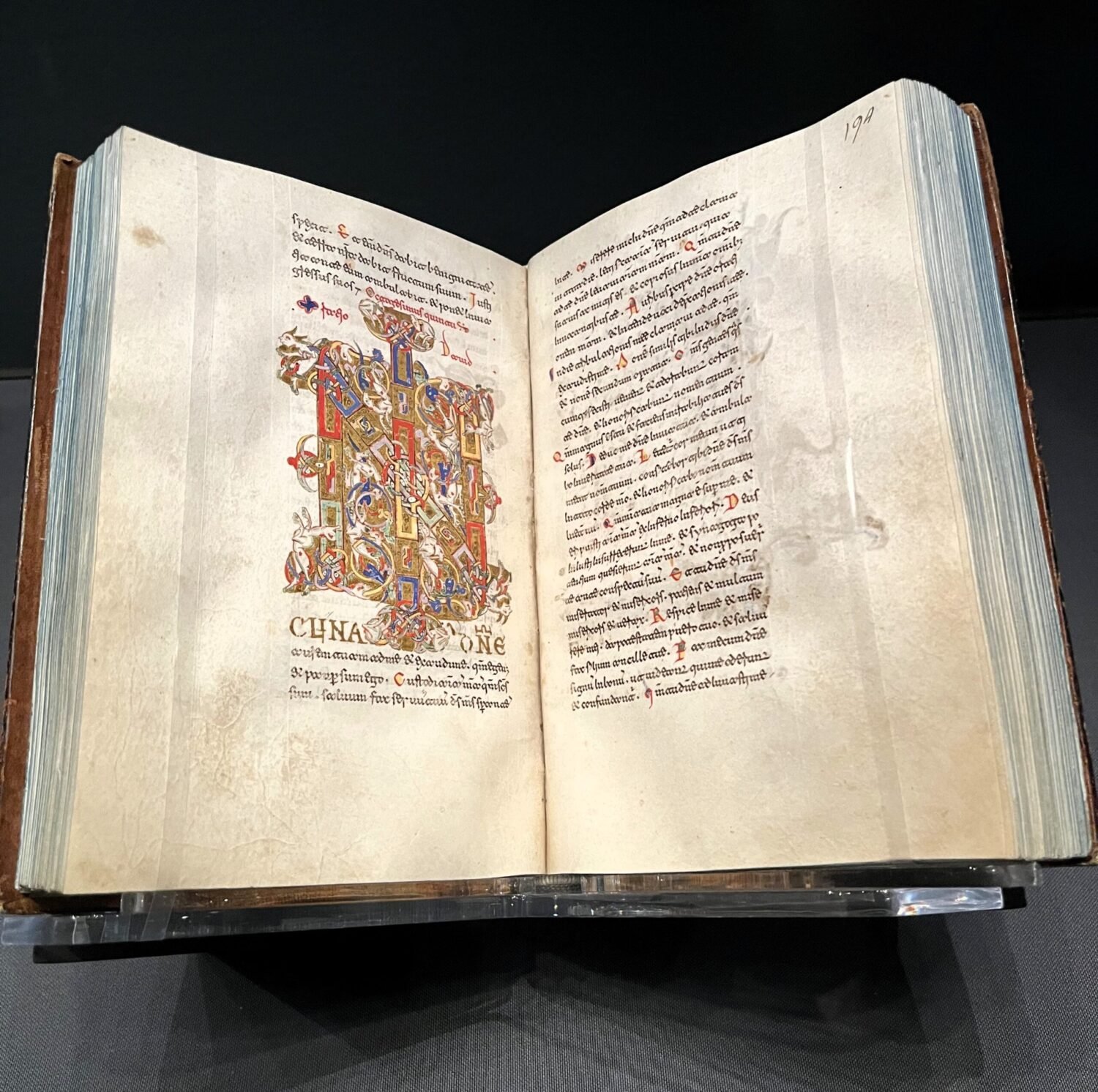

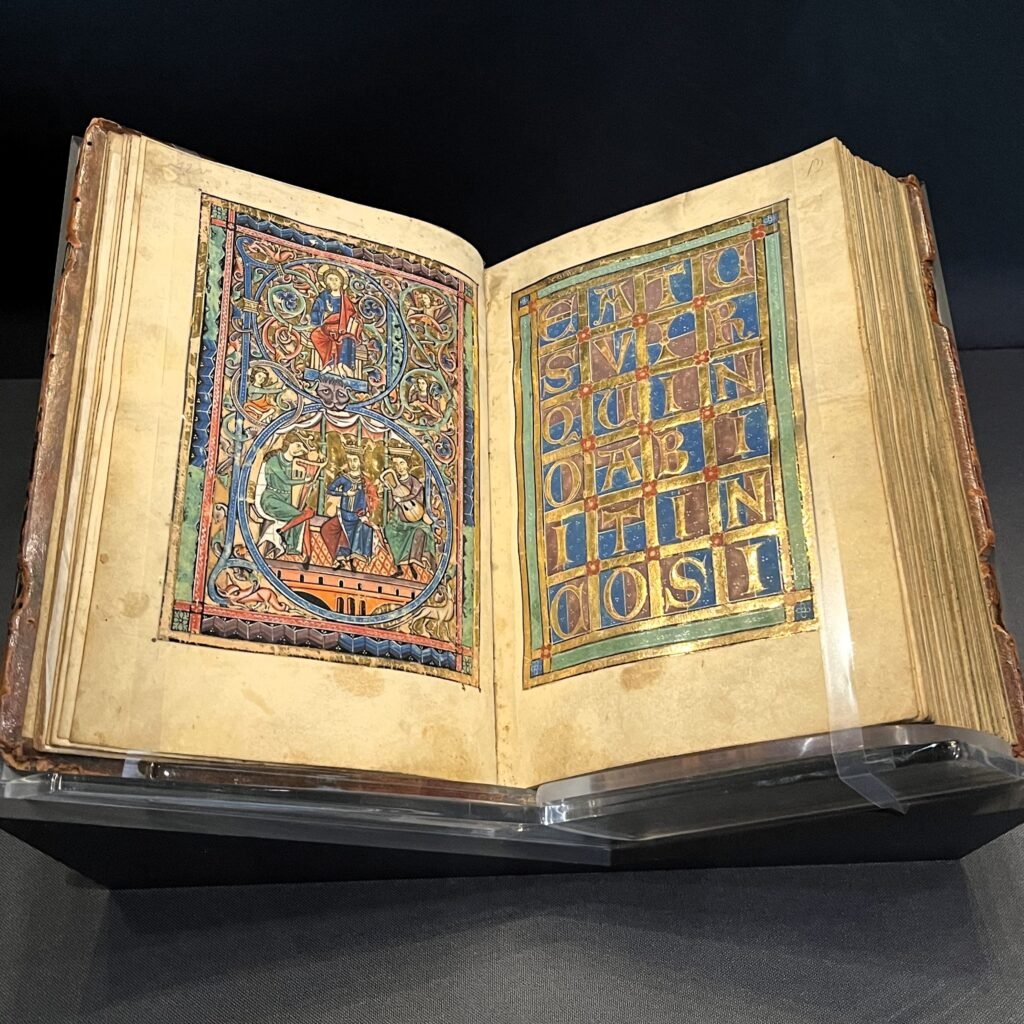

Initial B: Christ in Majesty and David with Musicians | Date: 1240-50 | Country: Germany | Artist: Unknown | Text: Psalter (in Latin)

These two pages contain a series of codes for the viewer to untangle. Enclosed in the loops of the large letter B at left are the enthroned figure of Christ (top) and musicians surrounding King David (bottom). At right, golden letters spell out Latin words, beginning (B)eatus vir… All these elements help identify the first Psalm in the Bible.

Image Codes

Medieval art is famously symbolic, and the pages of illuminated manuscripts were no exception. Artists used visual signs, such as specific colors, attributes, and personified figures, to represent theological ideas or identify characters.

For instance, a woman holding a chalice might represent the Church, while a lion could point to Saint Mark. These images weren’t meant to be realistic but rather conceptual: they helped communicate complex ideas in ways that were both immediate and memorable. In a world where people were not literate, image codes were key to communication.

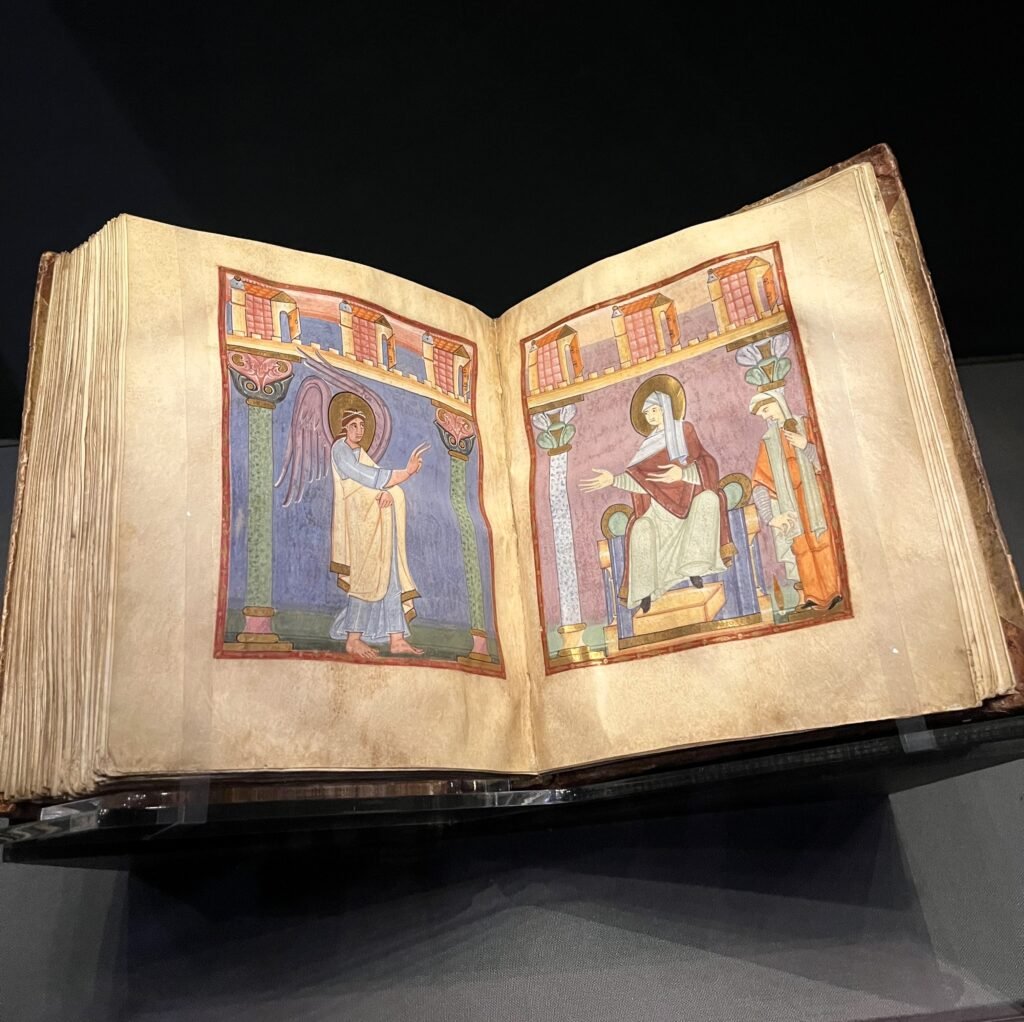

The Annunciation | Date: 1053 | Country: Germany | Artist: Unknown | Text: Irmengard Codex

Colors carried important meanings in medieval art. In this Christian scene, the divine and human worlds meet when the archangel Gabriel, God’s messenger, arrives to tell the Virgin Mary that she will become Jesus’ mother. The background colors markedly distinguish the two realms. Blue behind the angel represents the heavenly sphere, while purple surrounding Mary signifies the earthly domain.

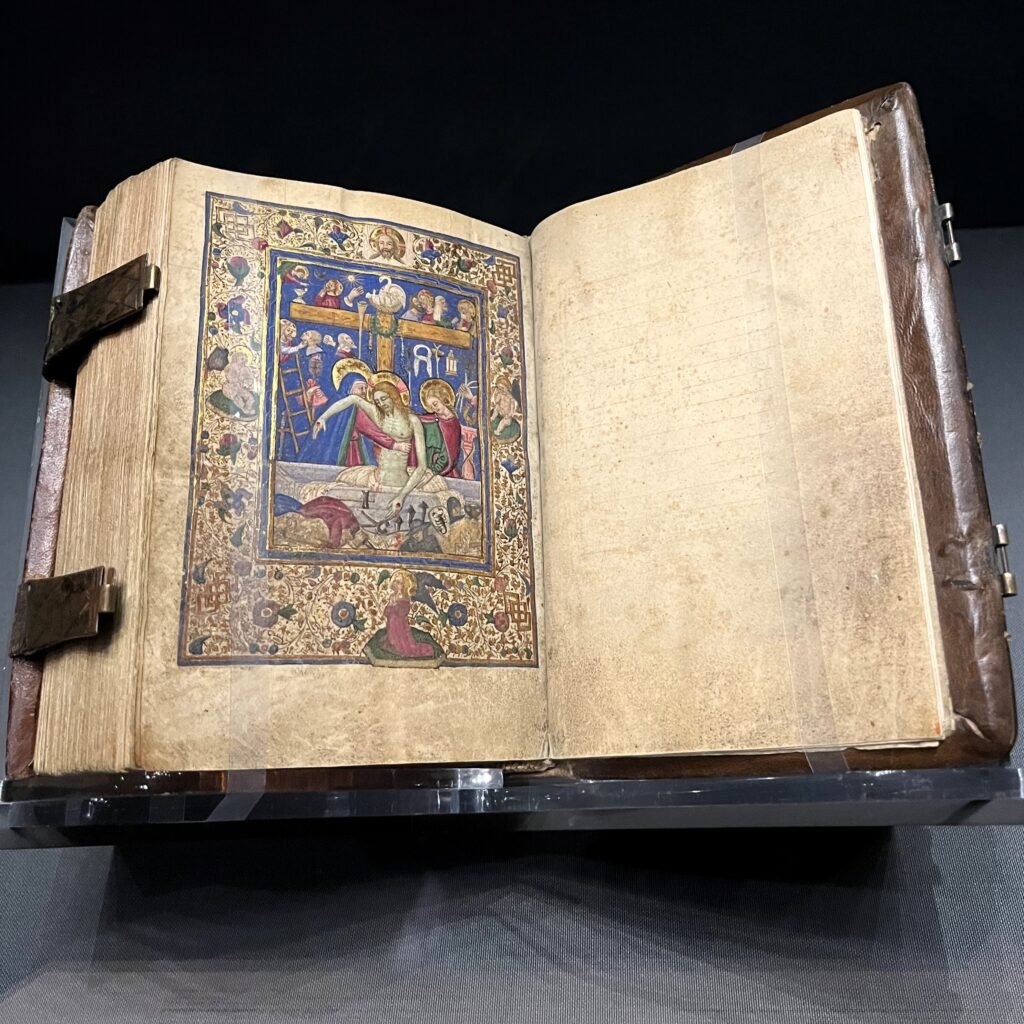

The Pieta | Date: About 1460 | Country: Italy | Artist: Unknown | Text: Book of hours (in Latin)

Objects depicted in an image help viewers identify a figure or a scene… as long as the audience understands the symbolism. In this manuscript, Christ’s limp body is surrounded by items representing different moments in the story of His suffering and death.

Schematic Codes

Modern life is full of visual systems that organize information, chart, graphs, calendars, etc. Medieval manuscripts had their own versions of these, often rendered with stunning creativity.

The exhibit showcased examples of early indexes, calendars marking feasts and saints’ days, and musical scores meant for monastic chants. These schematic codes didn’t just store information, they made it accessible, meaningful, and sometimes even beautiful. The care with which they were created suggests that beauty, order and mystery were deeply intertwined in the medieval imagination.

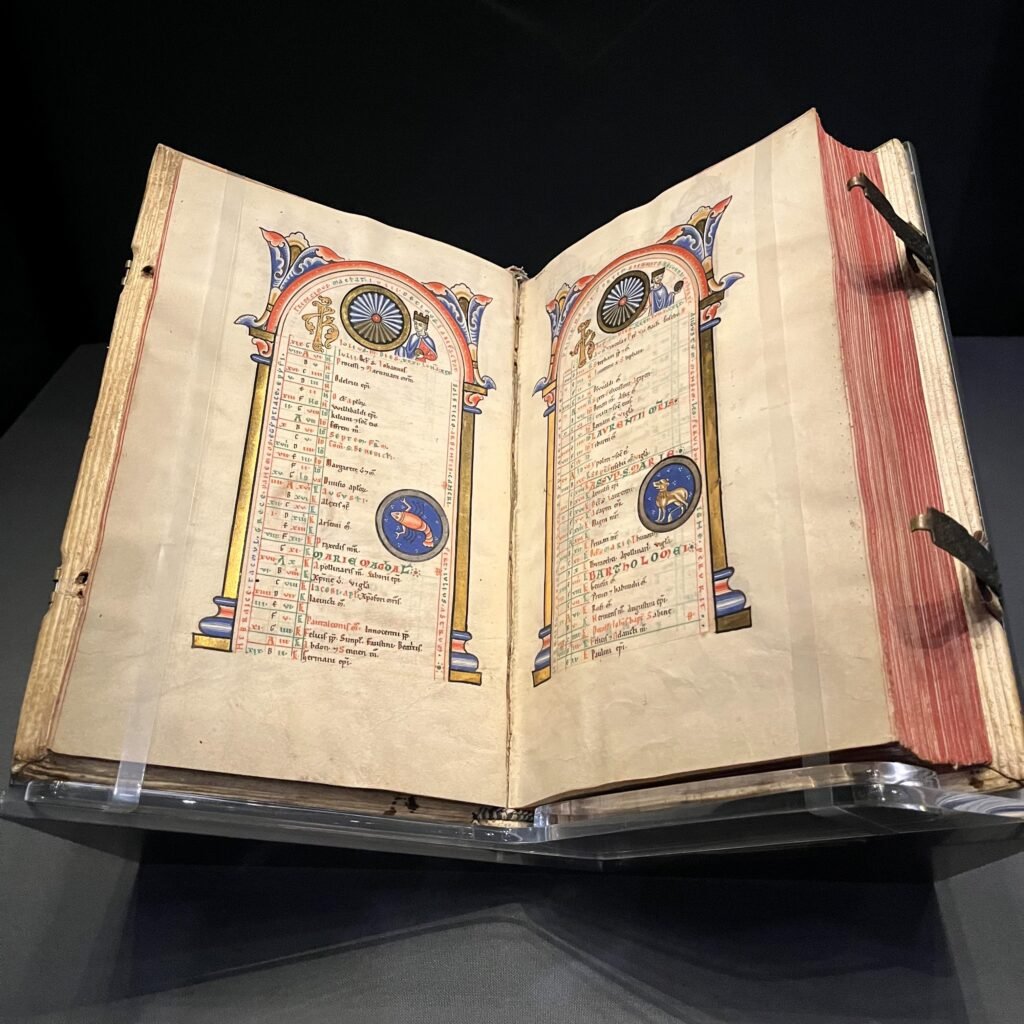

Calendar Pages for July and August | Date: 1170s | Country: Germany | Artist: Unknown | Text: Stammheim Missal (in Latin)

The movement of the sun, moon, and stars provides natural laws for the passage of time. This medieval calendar, in which each page represents one month, contains information about individual days, the signs of the zodiac, and even the average amount of daylight, which is conveyed in a circle resembling a clockface.

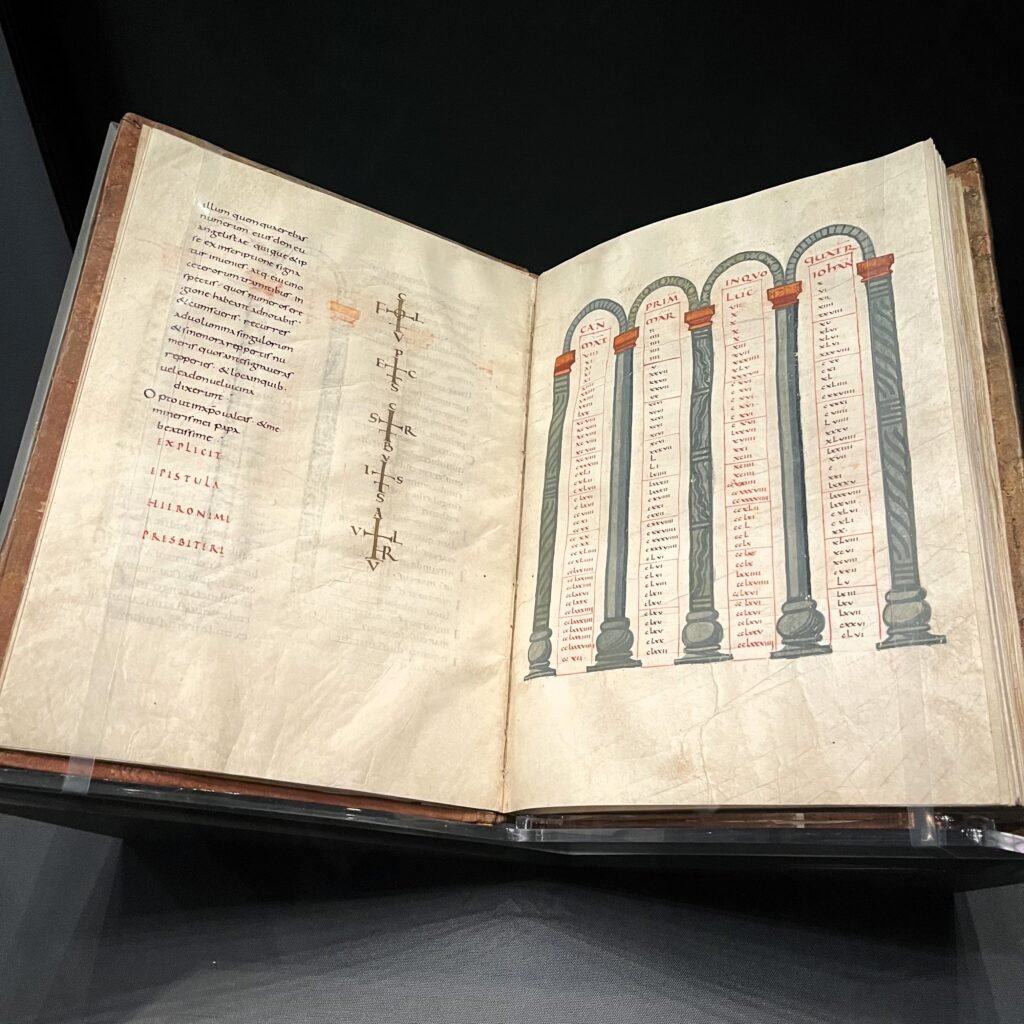

Text Page with Monograms Canon Table Page | Date: 826-38 | Artist: Unknown | Text: Gospel book (in Latin)

Each cross-shaped monogram on the left page spells out part of a word or name, which, taken together, form a sentence revealing the original owner of this early-medieval manuscript as well as the name of the scribe.

Information in this post is based on the Symbols and Signs: Decoding Medieval Manuscripts | Getty Exhibitions Photos include images I took during my visit, as well as select materials from the exhibit.